The Latest in the Battle for US Drug-Pricing Reform

Drug-pricing reform in the US is on the table once again as Congress and the Biden Administration seek to move forward with a new plan. What’s in the plan?

Drug-pricing reform: the latest turn

Last week (November 2, 2021), members of Congress and the Biden Administration agreed to a new plan for drug-pricing reform, a plan considered more moderate than ones that had been put forth under earlier proposals. The new plan would allow the US government to negotiate, with certain limitations, drug prices under Medicare, the US government healthcare program for people 65 and older and disabled people; impose a cap for out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs under Medicare; and set limits on annual increases in drug prices under Medicare.

The new plan scales back what had been proposed for drug-pricing reform under the Build Back Better Act, which is President Joe Biden’s proposed $1.75-trillion spending plan and which continues to be debated in Congress. With the likelihood of drug-pricing measures as first outlined in that bill facing opposition, the Administration and Democratic members of the US House of Representatives and the US Senate put forth a new framework for drug-pricing reform. That framework was announced last week (November 2, 2021) and would serve as the basis for new proposed legislation.

The new plan scales back drug-pricing reforms under earlier legislation. The House of Representatives passed a drug-pricing reform bill in December 2019, the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act (H.R. 3), which did not advance in the Senate. A key measure in that bill would have required the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to negotiate drug prices directly with manufacturers, subject to a cap based on international reference pricing. In September (September 2021), The Reduced Costs and Continued Cures Act was introduced in the House of Representatives as an alternative to H.R. 3. While retaining certain key provisions of H.R. 3, such as allowing the HHS to negotiate drug prices under Medicare and capping out-of-pocket drug costs, it scaled back some of those provisions.

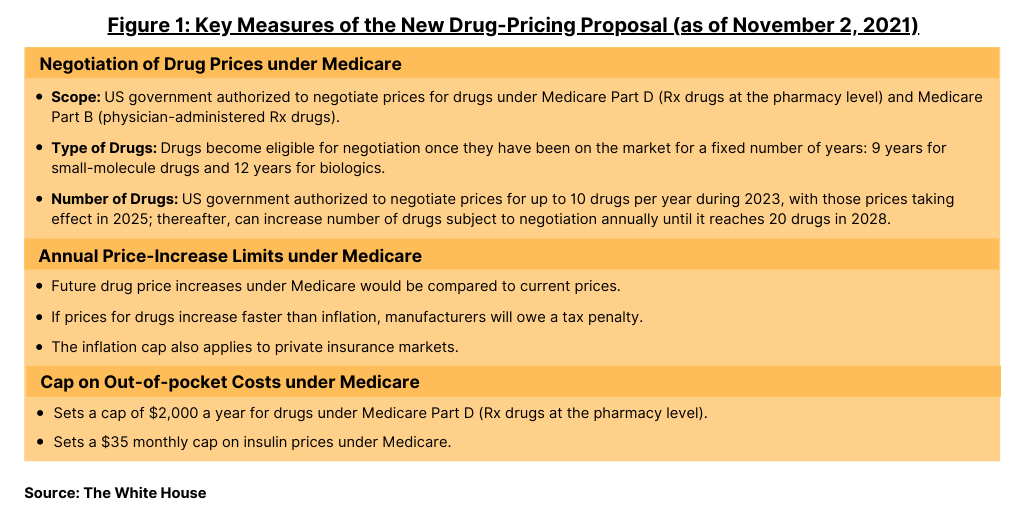

The new plan, supported by leadership in both the House and Senate and by the Biden Administration, is now the key policy proposal on the table for drug-pricing reform in the US. Key measures of the proposed plan are outlined below and in Figure 1.

Negotiation of drug prices under Medicare

Under the new plan, the US government would be authorized to negotiate prices for drugs under Medicare Part D (prescription drugs at the pharmacy level) and for drugs under Medicare Part B (physician-administered prescription drugs). Drugs become eligible for negotiation once they have been on the market for a fixed number of years: nine years for small-molecule drugs and 12 years for biologics. The maximum price Medicare would pay would be 75% of what commercial US insurers pay on average for drugs that have been on the market between nine and 12 years, with the maximum decreasing the longer the drug has been available.

The US government would be authorized, under Medicare, to negotiate up to 10 drugs per year during 2023, with those prices taking effect in 2025. The number of drugs that will be subject to Medicare negotiations will increase annually until it reaches 20 in 2028. The government will select from a list of drugs it spends the most on in Medicare Part B, which covers physician-administered drugs, and Medicare Part D, which covers most prescription drugs sold at the pharmacy level. The new plan would also establish a clearly defined negotiation process, and drug companies that refuse to negotiate will owe an excise tax.

Prior proposals had originally set a maximum price of 120% of the average of what other wealthy nations pay for the same drug under an international drug-pricing reference model. In addition, earlier proposals would have allowed negotiations for at least 50 and up to 250 of the costliest drugs under Medicare and allow the government to fine companies which refused to negotiate, failed to agree on a price, or overcharge after agreeing on a price.

Limits to price increases tied to inflation

The new plan would impose a tax penalty if drug companies increase their prices faster than inflation. Starting when the associated bill becomes law, future drug price increases would be compared to their current prices. If prices for drugs under Medicare Part B (physician-administered drugs) and Medicare D (prescription drugs at the pharmacy level) increase faster than inflation, manufacturers will owe a tax penalty. The inflation cap also applies to private insurance markets.

Cap on out-of-pocket costs under Medicare

Under current Medicare provisions, there is no cap on how much Medicare recipients pay for prescription drugs. The new plan puts a cap of $2,000 a year for their drugs under Medicare Part D, the prescription drug benefit under Medicare. The plan would also set a $35 monthly cap on insulin prices under Medicare.

Industry feedback

While both the innovator-drug and generic-drug industry support measures to lower out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs under Medicare, they oppose measures that would allow for the US government to negotiate drug prices under Medicare and to set an inflation cap on drug prices on the basis that it would respectively limit new product development and access to generics and biosimilars.

“This drug pricing plan is not the balanced approach we need to build a better, more affordable health care system,” said Stephen J. Ubl, President and CEO of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), in a November 8, 2021, statement. PhRMA represents the large innovator, research-based bio/pharmaceutical companies. “Instead, it will make a broken system even worse. It will undermine important incentives that encourage continued innovation after a medicine is first approved, innovation that often leads to better treatments and health outcomes for patients. The plan creates perverse incentives that will discourage the development of lower-cost generic medicines and biosimilar treatments. It also fails to address the roles PBMs [pharmacy benefit managers] and insurers play in forcing patients to pay more than they should for their medicines.”

“This drug pricing plan is not the balanced approach we need to build a better, more affordable healthcare system.”

—Stephen J. Ubl, President and CEO, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America

The Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO), which represents large and smaller bio/pharmaceutical companies, also opposes the plan. “We have long fought for legislation to help patients with their out-of-pocket costs,” said Dr. Michelle McMurry-Heath, President and CEO of BIO, in a November 4, 2021, statement. “Policymakers said that was their intention as well—and said that would be reflected in this ‘deal.’ However, after reading through the nearly 3,000-page bill, it seems as if they have continued to insist on using a price-control scheme reminiscent of HR-3, which was rejected for being too extreme. CBO [Congressional Budget Office] explicitly stated that legislation would reduce the number of new drugs for patients.”

In her statement, BIO’s McMurry-Heath goes on to say: “…[W]e strongly support legislation that reduces what patients pay out-of-pocket for their medicines and ensures more people, in more communities, can access groundbreaking medical breakthroughs. This ‘deal’ falls far short of this commitment.”

“AAM strongly opposes an approach to direct negotiations in Medicare that would undermine biosimilar and generic development.”

—Dan Leonard, President and CEO, Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM)

The generics industry also opposes the plan, mainly for measures allowing the US government to directly negotiate the pricing for drug under Medicare and inflation-based caps, outlined Dan Leonard, President and CEO of the Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM), which represents generic-drug and biosimilar companies and manufacturers, in a November 2, 2021, statement. “AAM strongly opposes an approach to direct negotiations in Medicare that would undermine biosimilar and generic development,” he said. “Combined with inflation-based rebates on generics and biosimilars, the reforms being considered would upend the competitive framework envisioned with Hatch-Waxman and BPCIA [the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act] and threaten sustainable patient access to more affordable medicines.”