Evaluating FDA’s Foreign Mfg Inspections

A recent US government report evaluated the FDA’s process for for-cause inspections of foreign drug-manufacturing facilities. Although the FDA has made changes to improve the process, Congress and others have raised concerns. What did the review show?

FDA’s foreign inspection process: making progress or not?

The US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) oversight responsibility has become increasingly complicated because many drugs used in the US are manufactured overseas. Approximately 74% of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturers and 54% of finished goods manufacturers are located outside the US, according to information from the FDA. In 2017, the FDA began making changes to its foreign inspection program, and last month (June 2022), the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released a report that examined for-cause inspections of foreign drug-drug manufacturing facilities. For-cause inspections are triggered when the FDA has reason to believe that a facility has serious manufacturing quality problems or when FDA wants to evaluate corrections that facilities have made to address previous violations.

Specifically, the OIG of the HHS wanted to determine whether: (1) time frames for the foreign for-cause drug inspection process improved after FDA implemented programmatic changes in 2017; (2) FDA’s foreign for-cause drug inspection process followed applicable policies and procedures, and (3) lead investigators conducting foreign for-cause drug inspections met FDA’s training requirements.

In 2017, the FDA made two programmatic changes to its foreign inspection program: (1) it restructured the office that is responsible for conducting inspections to better respond to challenges arising from global markets and an increasingly complex legal environment and (2) the FDA implemented internal policies to improve collaboration among the FDA offices involved in the foreign inspection process.

The first programmatic change was a structural realignment of FDA’s Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA) and entailed a realignment from a geography-based model to a program-based model organized around FDA-regulated products. Under the realignment, management and staff, including investigators, are assigned to inspections based on their specialized knowledge to better respond to challenges arising from more global markets and an increasingly complex legal environment.

The second programmatic change was a new internal policy, the Integration of FDA Facility Evaluation and Inspection Program for Human Drugs: A Concept of Operations (ConOps). This internal policy is an agreement between FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research and ORA regarding the domestic and foreign pre- and post-approval, surveillance, and for-cause inspection processes for human drug facilities. According to the FDA, ConOps was implemented to enable CDER and ORA to more effectively manage and oversee the growing complexity of pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Congress and others seeking improvement

Despite these programmatic changes, Congress has continued to express concerns about the safety of certain drugs manufactured overseas and the challenges that the FDA faces with its foreign drug inspection process. In February 2019, Congress sent a letter to the FDA requesting a briefing on FDA’s efforts to conduct foreign inspections, and there have been legislative proposals to address the issue, with one issue being not announcing in advance inspections of foreign manufacturing facilities, similar to the process used for unannounced inspections at US-based facilities.

Earlier this year (January 2022), Senators Mike Braun (R-IN) and Joni Ernst (R-IA) introduced the Creating Efficiency in Foreign Inspections Act (S. 3509), which proposes to eliminate the FDA’s practice of preannouncing foreign surveillance inspections unless notice is mandated by the host country or is required to protect public health. The requirements of the bill apply only to surveillance inspections and not to preapproval, prelicensure, or for-cause inspections. The bill was referred to the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pension, where it remains.

The frequency and number of inspections of drug-manufacturing facilities located outside the US is an important issue not only to improve regulatory oversight but is also considered important from a business view as a means to create a more competitive playing field among drug manufactures. Facilities that manufacture drugs for the US market have to be inspected by FDA, but there has been a long-standing difference in the level of domestic and foreign inspections.

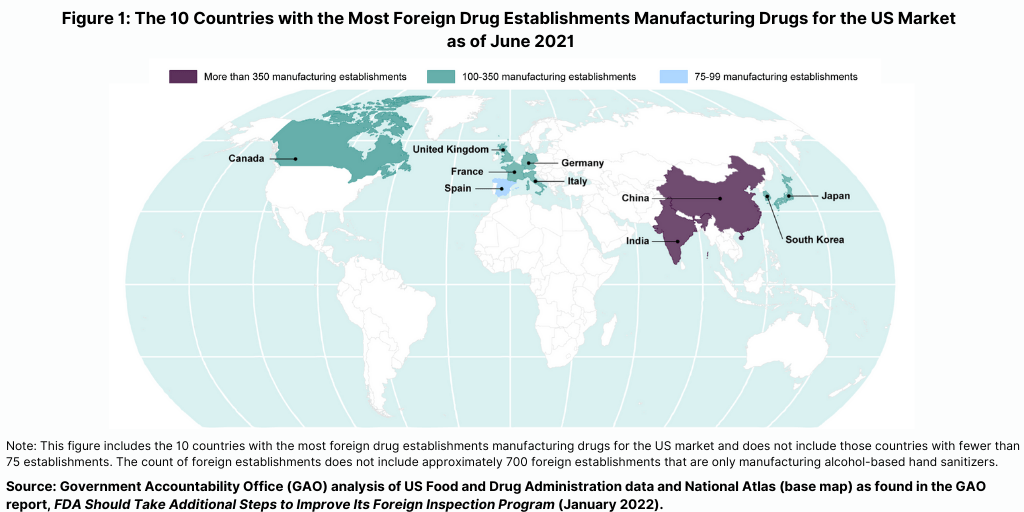

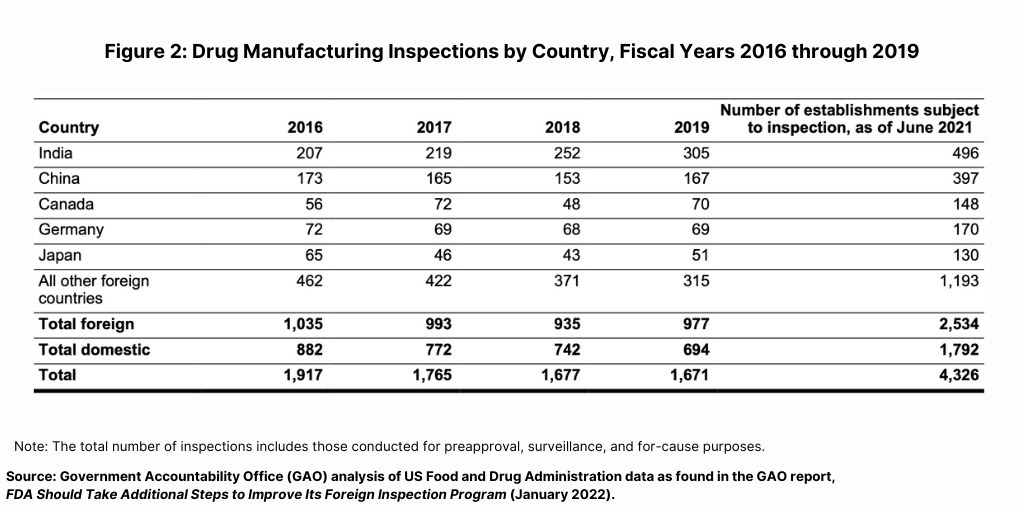

The FDA conducts the largest number of foreign inspections in India and China, where more than one-third of foreign establishments supplying the US market are located (see Figure 1), according to report released in January (January 2022) by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO), which evaluated the FDA’s program for foreign inspections. The GAO is a legislative branch government agency that provides auditing, evaluation, and investigative services for the US Congress. In its report, it concluded that the FDA needs to do more to improve its oversight of foreign drug-manufacturing facilities.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, foreign drug inspections had begun to increase and the largest increase was in India (see Figure 2). In fiscal year 2019, the FDA began to increase the number of inspections of foreign drug-manufacturing establishments after decreases from fiscal years 2016 through 2018, according to the GAO report. In addition, the FDA continued to conduct more foreign than domestic inspections in each fiscal year from 2016 through 2019. In fiscal year 2019, the FDA continued to conduct the largest number of foreign inspections in India and China, with an increasing number of inspections conducted in India, where about 20% of foreign establishments subject to inspection were located in recent years (see Figure 2).

A key finding from the GAO report was that the level of deficiencies in facilities inspected—both domestic and foreign—were similar, with most facilities having deficiencies that did not warrant regulatory action. After each inspection, the FDA classifies the inspection into one of three categories based on its determination of whether any deficiencies identified during the inspection are serious enough to warrant regulatory action. The three categories are: (1) no action indicated (NAI); (2) voluntary action indicated (VAI), and (3) official action indicated (OAI).

From fiscal years 2018 through 2020, the FDA identified deficiencies in the majority of both foreign and domestic inspections, but, in most cases, the agency determined that the deficiencies did not warrant regulatory action). Approximately 66% of all foreign inspections (1,502 of 2,286 inspections) identified deficiencies at the establishment (as identified by the percentage of inspections it classified as VAI or the more serious OAI), of which only 16% (244 of 1,502 inspections) had deficiencies serious enough to warrant regulatory action (an OAI classification). Similarly, FDA data showed that the agency determined that 64% of domestic inspections (1,167 of 1,812 inspections) it conducted during this same time period identified deficiencies, of which 17% (203 of 1,167 inspections) had deficiencies serious enough to warrant regulatory action.

In its report, the GAO acknowledged that the FDA faces unique challenges for conducting foreign inspections compared to domestic inspections, such as having to pre-announce foreign inspections due to travel and jurisdictional issues, language barriers, and talent and recruitment challenges to maintain an inspectional workforce for foreign inspections. The FDA is in the process of developing plans to conduct pilot programs intended to address these issues.

New report looks at foreign for-cause inspections

The new report by the OIG of the HHS looked specifically at foreign for-cause inspections. To make its evaluation, the OIG of the HHS reviewed all 64 foreign for-cause drug inspections that occurred during the period January 1, 2016, through March 31, 2017, and all 68 foreign for-cause drug inspections that occurred during the period January 1, 2018, through March 31, 2019. To determine whether inspection efficiency improved following FDA’s implementation of programmatic changes in 2017 for each of the inspections covered by its audit, the OIG calculated the time it took the FDA to complete the following steps: (1) initiate the inspection; (2) conduct the onsite inspection; (3) complete the initial and final classifications; (4) take further action against the inspected facilities when further action was needed (including issuing Warning Letters, issuing import alerts, and holding regulatory meetings); and (5) conducting follow-up inspections at facilities previously classified as OAI and not subject to an import alert.

What the OIG found: time frames for inspection activity

The OIG of the HHS found that FDA’s time frames for completing the steps in the foreign for-cause drug inspection process generally improved after it implemented the programmatic changes. However, it found that: (1) FDA did not always follow its policies and procedures for foreign for-cause drug inspections and (2) FDA could not provide documentation to support that all lead investigators completed the required training before they conducted inspections.

Specifically, the OIG found that the times to: (1) initiate inspections, (2) classify inspections, (3) issue Warning letters, and (4) hold regulatory meetings improved after implementing programmatic changes. However, the time to conduct the onsite inspection did not change after programmatic changes, and the times to: (1) issue import alerts and (2) follow up at inspected facilities previously classified as OAI did not improve after the programmatic changes.

Import alerts. Specifically, the OIG found that before the programmatic changes, the FDA issued nine import alerts on average 84 days after the end of a foreign for-cause drug inspection. After the programmatic changes, the FDA issued eight import alerts on average 136 days after the end of the foreign for-cause drug inspection.

Follow-up at inspected facilities. Before the programmatic changes, the FDA conducted follow-up inspections at 11 facilities on average 329 days after the FDA classified the prior inspection as OAI and after FDA finalized any subsequent actions. After the programmatic changes, as of September 14, 2021, the FDA conducted follow-up inspections at six facilities on average 460 days after OAI classification had been finalized and any actions taken.

What the OIG found: following FDA policies and procedures

The OIG found that the FDA did not always follow its policies and procedures for foreign for-cause drug inspections after it implemented the programmatic changes. Specifically, it found that the FDA:

• Did not follow its policies and procedures related to the timeliness of inspection classification for 40% of foreign for-cause drug inspections;

• Did not follow its policies and procedures related to the timeliness of Warning Letters for 33% of Warning Letters issued as a result of foreign for-cause drug inspections;

• Generally followed its policies and procedures related to the timeliness of regulatory meetings for 90% of regulatory meetings resulting from foreign for-cause drug inspections; and

• Did not indicate in the establishment inspection reports whether an inspection was announced in accordance with its policies and procedures for eight foreign for-cause drug inspections.

What the OIG found: training of lead FDA investigators

In its audit, the OIG said that the FDA could not provide documentation to support that all lead investigators completed the required training before they conducted inspections. Specifically:

• Two lead investigators, who each conducted one inspection, did not complete required training before they conducted inspections; and

• Six lead investigators’ training records did not include documentation showing that required training was completed. Specifically, the FDA could not provide documentation to support that six of the 65 lead investigators for the inspections that the OIG reviewed completed the required training and passed a Level 1 Performance Audit, which is needed to obtain a Level 1 Investigator Certification.

OIG recommendations to the FDA; FDA’s response

Based on its findings, the OIG of the HHS recommend that the FDA do the following:

• Identify and implement additional ways to improve the timeliness of its foreign for-cause drug inspection process;

• Consider streamlining the process for writing and reviewing establishment inspection reports to minimize potential delays due to unexpected events;

• Conduct an analysis of the workloads of individuals responsible for: (1) determining final classification; (2) issuing Warning Letters; and (3) holding regulatory meetings and address any potential issues identified by this analysis;

• Implement policies and procedures to ensure that lead investigators assigned to inspections have completed the Level 1 Investigator Certification Process;

• Ensure that supervisors review investigators’ qualifications and document that they meet applicable training requirements when the investigator training records do not exist; and

• Review the training records of the lead investigators that were outside the scope of the audit to verify that documentation supports either: (1) that the investigators completed the required training courses: Level 1 Performance Audit and Level 1 Investigator Certification; or (2) that investigators are recommended as “experienced investigators” by supervisors and have completed training courses equivalent to the current required training courses.

The OIG said that the FDA concurred with its recommendations and that the FDA is working to improve the timeliness of the overall foreign for-cause inspection process. Furthermore, pending approval by Congress, FDA stated that it has committed to goals regarding the timing of foreign facility follow-up inspections. FDA also stated that it is addressing ways to reduce the time spent writing and reviewing establishment inspection reports and that it is conducting a workload analysis for individuals responsible for determining final classification, issuing Warning letters, and holding regulatory meetings. The FDA also stated that it will soon begin implementing a new system to better document and track the qualifications and Level 1 Certification status of investigators.