Drug Supply Chains and US-Based Manufacturing

In the wake of the coronavirus outbreak, there is increased evaluation of global drug supply chains. Some members of Congress and the federal government are calling for ways to further incentivize domestic drug manufacturing in the US. What proposals are on the table?

Global pharmaceutical supply chains

The global nature of pharmaceutical supply chains and what that means for US policy has been a topic of discussion. Last fall (October 2019), Janet Woodcock, Director of the Center for Evaluation and Research (CDER) at the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), testified before the Subcommittee on Health, Committee on Energy and Commerce, US House of Representatives, to provide information on the US position in global pharmaceutical supply chains.

“Historically, the production of medicines for the US population has been domestically based,” said Woodcock in her testimony on October 31, 2019. “However, in recent decades, drug manufacturing has gradually moved out of the United States. This is particularly true for manufacturers of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), the actual drugs that are then formulated into tablets, capsules, injections, etc.”

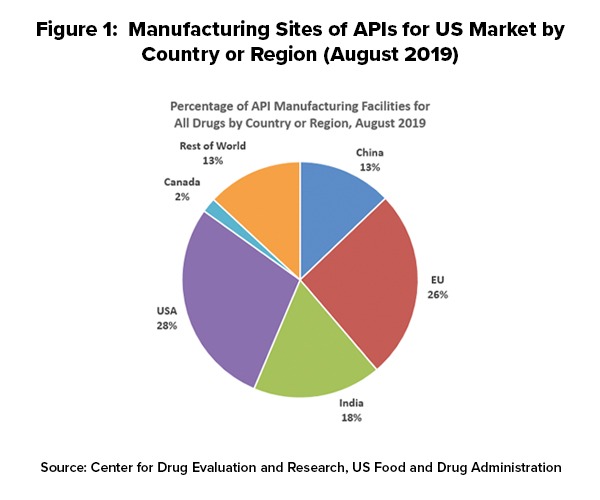

As of August 2019, 28% of the manufacturing facilities making APIs for US markets were based in the US. The remaining 72% of the API manufacturers supplying the US market were outside the US, which includes 13% in China (see Figure 1). The analysis applies to all FDA-regulated products, which includes prescription drugs (branded and generic), over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, and compounded medications.

Outside the US, the European Union (EU) represents the largest source of APIs manufactured for US-marketed drugs at 26%, representing the historical and current position of EU-based fine chemical and API manufacturers as well as offshore facilities of pharmaceutical manufacturers. India follows at 18% of APIs supplied to the US and then China at 13% (see Figure 1).

In explaining geographic shifts in API production for US-marketed drugs over the past decade, Woodcock pointed to a variety of factors, including lower-cost labor costs, as a major contributing factor. She cited a 2009 paper by the World Bank, “Exploratory Study on Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient Manufacturing for Essential Medicines,” which specified if a typical Western API company has an average wage index of 100, this index is as low as 8 for a Chinese company and 10 for an Indian company (note: this analysis, published in 2009, does not reflect subsequent cost adjustments or cost equalization since 2009). She also pointed to lower energy costs (electricity and coal) and lower water costs in China as well as a network of raw materials and intermediary suppliers that can provide lower shipping and transaction costs for raw materials.

Proposals for encouraging US-based pharmaceutical manufacturing

The interest by policymakers to incentivize companies to increase drug manufacturing in the US is part of a larger policy goal to increase all domestic manufacturing, including pharmaceutical manufacturing, but that goal has taken on further importance in evaluating global supply chains.

Earlier this month (March 2020), US Senators Robert Menendez (D-NJ) and Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) introduced bipartisan legislation, The Securing America’s Medicine Cabinet Act (S. 3432), to increase US-based manufacturing of APIs by encouraging and providing incentives for pharmaceutical manufacturing innovation and advanced pharmaceutical manufacturing. The proposed legislation authorizes $100 million to develop centers of excellence in advanced pharmaceutical manufacturing for developing innovation as well for workforce training. These centers would be partnerships between institutes of learning and the private sector. The funding is intended to further encourage drug manufacturers to spur innovations similar to those in other industries, such as automotive, aerospace and semiconductors, and bring drug manufacturing back to the US. The bill also calls for the creation of an Advanced Manufacturing Technologies Unit within the FDA to prioritize issues related to national security and critical drug shortages as well as create additional pharmaceutical manufacturing jobs in the US.

As in other manufacturing industries, the use of advanced manufacturing, which involves increased automation and other technologies, is seen as a way for US-based manufacturers to compete with other countries, particularly those that may provide lower production costs. This point was underscored by FDA’s Woodcock in her testimony before Congress last fall (October 2019). Speaking from a US public policy perspective, Woodcock noted that advanced manufacturing technology was an important element in achieving US competitiveness in API supply for US-marketed drugs. “Using traditional pharmaceutical manufacturing technology, a US-based company could never offset the labor and other cost advantages that China enjoys simply by achieving higher productivity,” she said in her testimony on October 31, 2019 before the US House Subcommittee on Health, Committee on Energy and Commerce, US House of Representatives. “However, FDA believes that advanced manufacturing technologies could enable US-based pharmaceutical manufacturing to regain its competitiveness with China and other foreign countries, and potentially ensure a stable supply of drugs critical to the health of US patients.”

As outlined by Woodcock, advanced manufacturing is a collective term for new medical-product manufacturing technologies that can improve drug quality, address shortages of medicines, and speed time-to-market. She explained that advanced manufacturing technology, which the FDA supports through its Emerging Technology Program, has a smaller facility footprint, lower environmental impact, and more efficient use of human resources than traditional technology, and includes technologies such as continuous manufacturing and 3-D printing.

Other legislative proposals

Other members of Congress also have introduced legislation to address the US pharmaceutical and medical products supply chain. Another bill introduced in the US House of Representatives earlier this month (March 2020) would require drug manufacturers of essential drugs and manufacturers of medical devices to disclose source of origin for their products and other manufacturing reporting information. Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-WI) and Rep. Mark Pocan (D-WI) introduced the Medical Supply Chain Security Act (H.R. 6049). This bill would provide the FDA authority to analyze sourcing locations of medical products. Companion legislation (S. 3343) in the Senate was introduced late last month (February 2020) by Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO).

The bill would provide new authority to the FDA to request information from manufacturers of essential drugs or devices regarding all aspects of their manufacturing capacity, including sourcing of component parts, sourcing of APIs, use of any scarce raw materials, and any other details the FDA deems relevant to assess the security of the US medical product supply chain.

With regard to medical devices, the bill also requires that manufacturers report imminent or forecasted shortages of medical devices to the FDA just as they currently do for drugs. This new information on devices would be added to the FDA’s annual report to Congress on drug shortages. The bill would also allow the FDA to expedite the review of essential medical devices that require pre-market approval in the event of an expected shortage reported by a manufacturer.

Last year (October 2019), Reps. John Garamendi (D-CA) and Vicky Hartzler (R-MO) introduced the Pharmaceutical Independent Long-Term Readiness Reform Act (H.R. 4710) that would require the US Department of Defense to identify the vulnerabilities faced by the country’s medical supply chains and to only purchase US-made raw materials, medicines, and vaccines for the military.

The bill would further require that not later than one year after the date of the enactment of the legislation, the US Secretary of Defense, in consultation with the heads of other appropriate federal departments and agencies, submit to Congress a report on vulnerabilities to the US medicine supply chain. The report would require the following:

- (1) an identification of any finished drugs and their essential components, including raw materials, chemical components and active ingredients necessary for the manufacture of medicines whose supply is at risk of disruption during a time of war or national emergency;

- (2) an identification of shortages of finished drugs essential for combat readiness and force protection;

- (3) an identification of the defense and geopolitical contingencies that are sufficiently likely to arise that may disrupt, strain, compromise, or eliminate supply chains of medicines and their essential components and recommendations for reasonable preparation for the occurrence of such contingencies;

- (4) an assessment of the resilience and capacity of the current supply chain and industrial base to support national defense upon the occurrence of the contingencies, including with respect to the following: the manufacturing capacity of the US; gaps in domestic manufacturing capabilities, including non-existent, extinct, threatened, and single-point-of-failure capabilities; and supply chains with single points of failure and limited resiliency;

- (5) legislative, regulatory, and policy changes necessary to avoid, or prepare for, contingencies identified in the report; and

- (6) recommendations to diversify supply away from complete dependency on sources of supply in competitor countries and politically unstable countries that may cut off US supply, and address critical bottlenecks and mitigate single points of failure.

Executive action

Meanwhile, Peter Navarro, Assistant to the President and Director of the Office of Trade and Manufacturing, said in media interviews this week (week of March 16, 2020) that he was working with President Donald Trump to finalize an executive order that would provide long-term incentives for US-based companies to produce medications and medical supplies domestically in the US. The strategy behind a proposed executive action consists of a multi-facet approach that would require federal agencies to purchase US-produced pharmaceuticals and medical equipment, deregulation, and incentivizing new technologies to encourage domestic production of pharmaceuticals and medical equipment in the US.