Drug Pricing Front & Center Again in the US: Impact on Manufacturers

With less than a month before the Presidential and Congressional elections in the US, drug pricing is again front and center on the policy agenda. As different approaches to reduce prescription drug prices emerge, what would be the impact on drug manufacturers?

Evaluating drug-pricing reforms

The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO), a federal agency that provides independent budget and economic analysis to Congress, recently issued a report to evaluate a set of policy approaches aimed at reducing the average prices of prescription drugs distributed through retail channels in the United States. To generate a list of policy approaches to analyze, the CBO considered current and previous Congressional legislative proposals, major proposals from the policy community, and the academic literature on health policy and prescription drug markets. CBO also examined various prescription drug pricing policies that are used in other high-income countries.

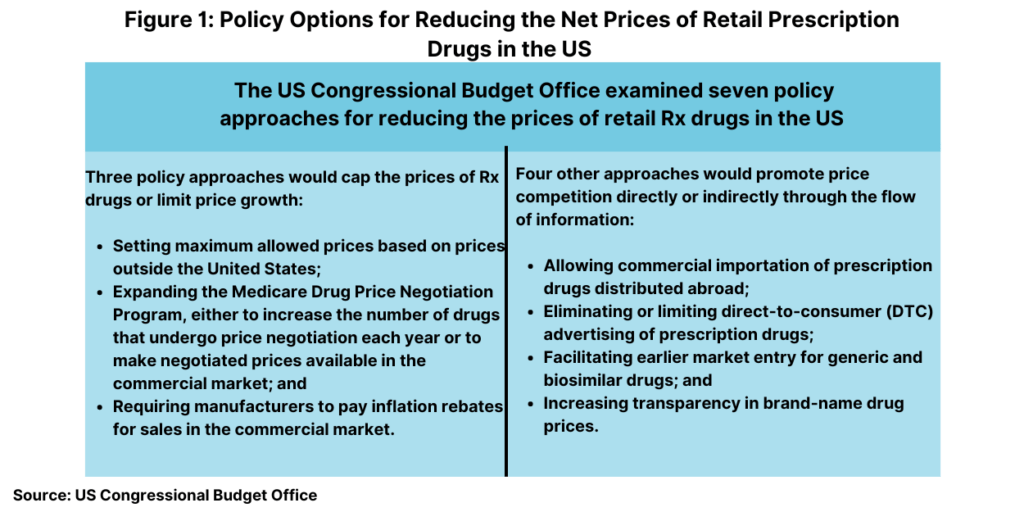

In all, it examined seven policy approaches in two broad categories: (1) approaches that would reduce the prices that drug manufacturers charge by capping those prices or limiting their rate of growth and (2) approaches that would promote price competition or affect the flow of information. Its analysis focused on prescription drugs purchased in retail settings, such as local brick-and-mortar pharmacies and mail-order pharmacies. Prices for drugs that are administered by physicians or other healthcare professionals in outpatient settings or hospitals are not within the scope of CBO’s analysis.

Figure 1 outlines the seven policy approaches examined by CBO and Table I (see end of article) evaluated the anticipated effect on average drug prices. CBO assessed how each of these seven approaches would affect average retail drug prices in 2031, when the total retail prescription drug market is projected to surpass $690 billion. For each approach, the effects would depend on the specifics of the policy (see Table I at the end of the article). The estimated effects of the approaches on price are characterized by size: An average price reduction of more than 5% is considered large; a reduction of 3% to 5% is moderate; a reduction of 1% to 3% is small; a reduction of 0.1% to 1% is very small.

Capping Rx drug prices or limiting prices growth

Broadly, three of the approaches would operate by capping the prices of prescription drugs or limiting price growth as outlined below.

Set maximum allowed prices based on prices outside the United States. In CBO’s assessment, a policy approach that used the prices of brand-name prescription drugs in high-income foreign countries to set maximum prices for those drugs would lower average prices in the US by a large amount (more than 5%).

Expand the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program. Under the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program, which was authorized by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, certain drugs will be made available in Medicare Part B or Part D (the US federal government program for healthcare for individuals 65 years or older) at prices negotiated between manufacturers and the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS). Each year, the HHS Secretary will select a number of drugs for price negotiation on the basis of total Medicare spending on the drugs and certain other criteria. Eligibility for price negotiation is limited to small-molecule drugs that have been on the market for at least seven years and have no generic competitors, as well as to biologic drugs that have been on the market for at least 11 years and have no biosimilar competitors. Each drug’s negotiated price is subject to a ceiling amount that is based on its previous price, rebate amount, and length of time on the market.

The first cohort of drugs to undergo price negotiation was announced in August 2023, their negotiated prices were announced in August 2024, and the negotiated prices will take effect in 2026. Beginning with the second cohort of drugs to undergo price negotiation (which will be selected in 2025), negotiated prices will take effect at the start of the second calendar year following selection. Medicare Part D plans will then be able to purchase the drug at its negotiated price, and enrollees’ cost sharing for the drug will be based on that price.

CBO examined two policies that would expand the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program. The first would increase the number of drugs whose prices get negotiated each year, which it says would lead to a very small (0.1% to 1%) or a small (1% to 3%) reduction in average drug prices in 2031. The second policy would make negotiated prices available to all commercial purchasers, which CBO would lower average prices by a small amount (1% to 3%).

Require manufacturers to pay inflation rebates for sales in the commercial market. CBO estimates that extending the Medicare Part D inflation rebate to sales in the commercial market would result in a small reduction (1% to 3%) in average drug prices in 2031.

Promoting price competition or affecting the flow of information

Four other approaches would operate by promoting price competition or by affecting the flow of information as outlined below.

Allow commercial importation of prescription drugs distributed outside the United States. This policy would require the HHS Secretary to allow the large-scale importation of prescription drug products from other countries. CBO estimates this would lead to a very small reduction (0.1% to 1.0%) in average drug prices in the United States.

Eliminate or limit direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising. CBO examined policies that would either eliminate direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising or prohibit it for three years after a drug’s initial approval for sale. CBO concluded that the result would be a very small reduction (0.1% to 1.0%) in average drug prices.

Facilitate earlier market entry for generic and biosimilar drugs. A diverse set of policies embodied in legislation recently introduced in Congress and analyzed by CBO would accelerate market entry for generic and biosimilar drugs. CBO estimates that these policies would reduce average drug prices by a very small amount (0.1% to 1.0%) or by less than 0.1%.

Summing up the impact on drug prices

As outlined above, the approach of setting maximum allowed prices based on prices outside the United States would result is the largest price reductions according to CBO’s analysis. It would reduce prices by more than 5% and possibly substantially more.

An approach that expanded the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program would lead to a small reduction (1% to 3%) or a very small reduction (less than 1%) in average prices. An approach requiring manufacturers to pay inflation rebates for sales in the commercial market would also lead to a small price reduction.

Four approaches would lead to a very small price reduction, no reduction, or a price increase. Those approaches are: (1) allowing commercial importation of prescription drugs distributed outside the United States; (2) eliminating or limiting direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising; (3) facilitating earlier market entry for generics and biosimilar drugs; and (4) increasing transparency in brand-name drug prices.

Impact on manufacturers

The CBO report concluded that although reducing drug prices would save money for patients and payers, it would reduce manufacturers’ expected revenue from drugs that are not yet on the market and would make investments in pharmaceutical research and development (R&D) less profitable, thus decreasing the number of new drugs developed and introduced.

Of the policies examined, the international reference pricing policy would dampen private investment in pharmaceutical R&D the most, according to the CBO analysis. It would greatly limit manufacturers’ ability to charge revenue-maximizing prices for affected drugs in the large US drug market, reducing both current revenue and expected future revenue. If prices increased in reference countries in response to the use of international reference pricing in the United States, that could offset part of the reduction in manufacturers’ revenue although the size of that offset would depend on the size of the international price response.

CBO estimates that expanding the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program in Part D would reduce manufacturers’ revenue from existing drugs as well as their expected future revenue from drugs developed later. The negative effect on R&D incentives would be limited, according to the CBO analysis because drugs would be eligible for price negotiation only after they had been on the market for several years. In CBO’s assessment, drugs developed later would experience smaller price reductions from negotiation than drugs currently on the market would.

Extending the Medicare Part D inflation rebate policy to the commercial market would have a smaller effect than expanding price negotiation would, according to the CBO analysis. It would not affect manufacturers’ expected revenue from new drugs developed in the future, but it would reduce their revenue from drugs already on the market, which would reduce their cash on hand and potentially increase their cost of investment capital. That policy could also create incentives for manufacturers to develop new versions of existing products because the new products would be tied to new benchmark prices, according to the CBO analysis.

For policy approaches that would promote price competition or affect the flow of information, allowing the commercial importation of prescription drugs that manufacturers distributed outside the United States would have a slight negative effect on R&D incentives, according to the CBO analysis. Brand-name drug manufacturers would lose revenue on sales of drugs that were redistributed under such a policy, reflecting the share of the price difference between the United States and foreign countries that would be retained by intermediaries and any savings passed on to drug purchasers. Because only a small volume of drugs would be available for redistribution under this approach, that revenue loss—and the policy’s effect on R&D investments—would be modest, according to the CBO analysis.

Eliminating or limiting direct-to-consumer advertising would have a very small effect on prices but would have a much larger effect on manufacturers’ future revenue. That is because, unlike other policy approaches examined in the CBO’s report, restricting direct-to-consumer advertising would affect the quantities of drugs consumed more than it would their prices, and manufacturers’ revenue depends on both quantities and prices. Consumers of prescription drugs would see only very small price reductions, similar in magnitude to those from other approaches such as allowing commercial importation, but manufacturers would experience larger reductions in revenue. As a result, this approach would dampen R&D incentives much more than other approaches with similarly sized effects on prices, according to the CBO analysis.

The policies that CBO examined that would promote earlier market entry for generic drugs and biosimilars would have very small effects on average prices. But the reduction in manufacturers’ revenue would primarily occur only after the drugs had been on the market for several years, which would attenuate any effect that such a policy would have on R&D, according to the CBO analysis. The composition of R&D could change if a policy discouraged the practice of product hopping, in which brand-name manufacturers develop modified versions of existing drugs to extend exclusivity protections.

The two policies aimed at transparency in prescription drug prices would each have a small dampening effect on R&D incentives. The first scenario that CBO examined, requiring manufacturers to publicly disclose rebates that they pay to insurers or pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), would reduce the variation in the net prices paid by different purchasers and probably cause the average net price to rise slightly. In CBO’s estimation, because manufacturers maximize their revenue by charging a wide range of prices to different purchasers, a policy that compressed net prices would cause total revenue to fall. The second scenario, requiring PBMs to share their drug price information with health insurers, would lower average prices by less than 1% and lead to a small decline in revenue.

Table 1: Anticipated Effect of Approaches to Reducing Rx Drug Prices

| Anticipated effect on average drug prices | Approach |

| Cap Prices or Limit Their Growth | |

| Large reduction: more than 5% or potentially substantially more | Set maximum allowed prices based on prices outside the United States |

| Expand the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program | |

| Small or very small reduction: 0.1% to 3% | Increase the number of drugs whose prices get negotiated each year |

| Small reduction: 1% to 3% | Make negotiated prices available to all commercial purchasers |

| Inflation Rebates | |

| Small reduction: 1% 35 | Require manufacturers to pay inflation rebates for sales in the commercial market |

| Promote Price Competition or Affect the Flow of Information | |

| Very small reduction: 0.1% to 1% | Allow commercial importation of prescription drugs distributed outside the US |

| Very small reduction: 0.1% to 1% | Eliminate or limit direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising |

| Very small reduction: 0.1% to 1%a | Facilitate earlier market entry for generic and biosimilar drugs |

| Increase transparency in brand-name drug prices | |

| No change (less than 0.1%) or a slight increase | Require public reporting of net prices for brand-name drugs |

| Very small reduction: 0.1% to 1% | Require pharmacy benefit managers to disclose net prices to insurers |