Drug Pricing Reform Back on the Policy Table in the US

Congress introduced legislation last week (March 23, 2021) to lower prescription drug pricing in the US. The measures include tying US drug pricing to other industrialized countries, allowing the US government to negotiate drug pricing under Medicare Part D, and allowing drug importation from Canada and other countries. What’s next?

New legislative proposals on the table

Last week (March 23, 2021), Congress introduced proposed legislation designed to lower the cost of prescription drugs in the US, thereby putting drug-pricing reforms back on the policy table in the US. The three bills build on measures in legislation passed by the House of Representatives in the last Congress in December 2019, the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act (H.R. 3), which did not proceed further in the US Senate.

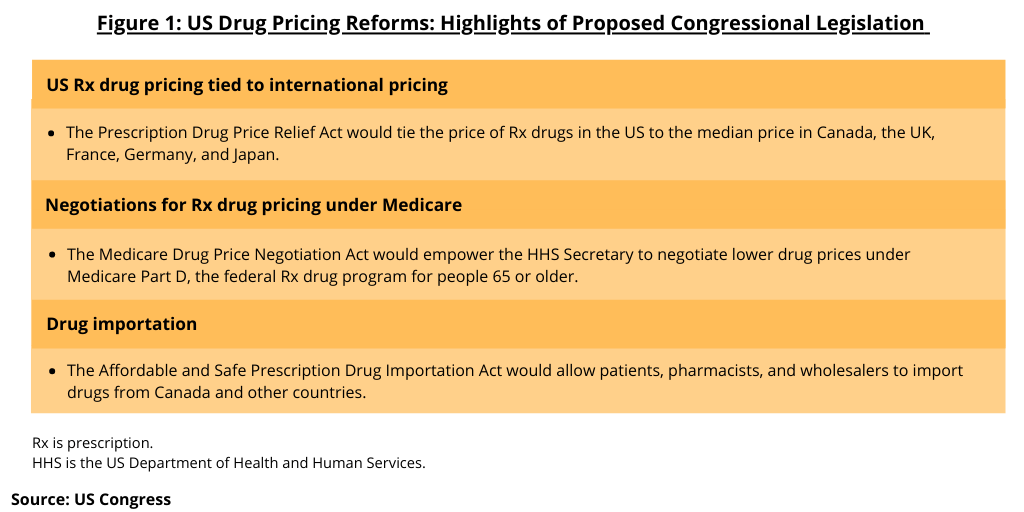

The legislative package includes three bills (see Figure 1): (1) The Prescription Drug Price Relief Act that would tie the price of prescription drugs in the US to the median price in Canada, the UK, France, Germany, and Japan; (2) The Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Act would authorize the Secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to negotiate lower drug prices under Medicare Part D, the federal prescription drug program for people 65 or older; and (3) The Affordable and Safe Prescription Drug Importation Act that would allow patients, pharmacists, and wholesalers to import drugs from Canada and other countries. The bills were introduced in the Senate by Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT), and in the House of Representatives by Reps. Ro Khanna, (D-CA), Lloyd Doggett (D-TX), Peter Welch (D-VT), and Cori Bush (D-MO), along with more than two dozen co-sponsors.

The introduction of these bills put into motion again the policy debate on drug pricing in the US. The legislative process in the US involves subcommittee and committee hearings with stakeholders as Congress considers these measures. The debate will also further involve the current Administration and its policy preferences as Congress debates the measures. Also, the manner in which any proposed legislation would proceed procedurally would also be a factor in the process. The specific measures in the proposed legislation are outlined below.

US drug pricing tied to international drug pricing

One important measure involves linking US drug pricing to international drug pricing. In the recently introduced legislation, The Prescription Drug Price Relief Act would require the HHS Secretary to annually identify the list of “excessively priced” patented, brand name drugs that are being sold in the US at prices higher than the median price in Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Japan. If the Secretary is unable to determine the median price of a drug in other countries, or if the Secretary believes that a drug is unaffordable even though its domestic price does not exceed the median price in other countries, the Secretary may still label the drug “excessively priced” after considering the several factors. These include: (1) the affected patient population; (2) the value of the drug to patients, including whether the price impacts access to the drug; (3) federal government subsidies and investments related to the drug; (4) costs associated with developing the drug; (5) whether the drug provided a significant improvement in health outcomes when approved; (6) the cumulative global revenues generated by the drug; (7) whether the price of the drug increased during any annual quarter by more than the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), which represents the US city average by expenditure category; and (8) other factors the HHS Secretary determines appropriate.

Under the bill, if the US price of a patented brand name drug exceeds the median price of the drug in other countries, or if the HHS Secretary otherwise determines the drug to be “excessively priced,” the HHS Secretary would be required to allow generic-drug manufacturers to make more affordable generic versions of the drug, regardless of any patents or market exclusivities that are in place for the drug. Any entity accepting a license to make a generic version of an “excessively priced” brand name drug would be required to pay a reasonable royalty to the holder(s) of the original drug patent at a royalty rate set the HHS Secretary.

In addition, under the bill, drug manufacturers would be required to submit annual reports to the HHS Secretary that include domestic and international pricing information for each brand name drug they manufacture. The HHS Secretary would review such information and would be required to create a public “excessive drug price database” listing each patented brand name drug, whether the US drug prices exceed the median prices in other countries, and other information. The HHS Secretary would then be required to provide an annual report to Congress and make the report publicly available that summarizes the year’s price review activities.

Negotiation of drug prices under Medicare Part D

Another piece of proposed legislation, The Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Act would authorize the HHS Secretary to negotiate lower drug prices under Medicare Part D, the US federal prescription drug program for people 65 or older. Under current law, the HHS Secretary is prohibited from negotiating lower drug prices on behalf of Medicare Part D beneficiaries, which is known as the “non-interference clause.” The bill would strike the non-interference clause and direct the HHS Secretary to negotiate lower prices with drug manufacturers that participate in Medicare Part D for certain drugs. These drugs would be those that meet certain conditions: (1) drug that place the most cost burden; (2) drugs that have significant price increases; (3) drugs that drive up Medicare Part D spending, and (4) drugs without competition.

In addition, the bill would direct the HHS Secretary to use the purchasing power of the federal government by using drug formularies to enhance competition. It would also allow Part D plans to use additional benefit design and formulary tools to secure additional discounts or rebates for beneficiaries. The bill would also establish fallback prices based on what other federal agencies and five foreign countries (Canada, the UK, Germany, France, and Japan) pay. These fallback prices would kick in automatically if negotiations with drug manufacturers are unsuccessful. The bill would also restore drug rebates for low-income beneficiaries that were eliminated when Medicare Part D was created in 2006.

Drug importation

The third bill, The Affordable and Safe Prescription Drug Importation Act would allow patients, pharmacists, and wholesalers to import drugs from Canada and other countries. The bill would authorize, within 180 days of the enactment of the legislation, the HHS Secretary to issue regulations allowing wholesalers, licensed US pharmacies, and individuals to import qualifying prescription drugs manufactured at US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-inspected facilities from licensed Canadian sellers. After two years, the Secretary would have the authority to permit importation from countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that meet specified statutory or regulatory standards that are comparable to US standards.

The bill would not permit importation of controlled substances, anesthetic drugs inhaled during surgery, or compounded drugs. Legally imported drugs would have to be purchased from a FDA-certified foreign seller, as defined by certain criteria, and have the same active ingredient(s), route of administration, and strength as drugs approved in the US. Certain types of drugs, such as certain biologics, could only be imported by wholesalers or pharmacies.

Additionally, the bill specifies that individuals importing a prescription drug would only be allowed to do so under certain conditions. With respect to drug importation from Canada, the drugs could only be imported from pharmacies licensed to practice pharmacy and dispense drugs in Canada. Also, individuals purchasing drugs for personal use would be limited to do so in quantities that do not exceed a 90-day supply, and they must have a valid prescription issued by a healthcare practitioner licensed to practice in the US.

Also, under the bill, the HHS Secretary would be required to issue a report to Congress and the public no later than one year after the date the rules for drug importation are finalized. The Government Accountability Office would also be required to conduct a study within 18 months following the final rule to analyze the implementation, including a review of drug-safety and cost-savings and expenses, and trans-shipment and importation tracing processes.